“Mommy, look.”

Dr. Hesh paused the interview to give the room a quick sweep through her goggles. She found her daughter twirling through the air with one of the ghosts. These appeared as shimmers of color in her display. “One minute, sweeting, Mommy’s almost finished working. We’ll go see Glair soon, okay?”

“Well, okay.”

It was good to see Lisse making friends again, even if she couldn’t take them home with her. Dr. Hesh turned back to the delicate man perched on a painted throne across from her. “Excuse us. I’d have someone else take Lisse if I could. She needs to be here.”

“Don’t worry,” said the man with a toothy grin. “Children are always welcome. They seem to like the warehouse and its many curiosities.”

“Of course. I only have time for a few more questions. You were telling me about the day you lost your theatre.”

Through the echovision goggles, the man and his chair appeared almost holographic, like the souls flapping their whisper-wings overhead, but he was tangible. His sideburns flared out to frame his plump face in dramatic contours; the hair had been growing and shrinking all through the interview. Like all Darkin, he was entirely blind. Not even the Light could restore his vision. He made decisive but enigmatic gestures as he spoke.

“Our precious theatre. I couldn’t bear the thought of telling my partners we had to give it up. They’re a sensitive group. We had Rasinsei planned for the next week, a beautiful tragedy with fireworks, three hundred floor-to-ceiling scrolls, and two of the empire’s finest actors. The production had already suffered setbacks, as I outlined before, and it would break their spirits to hear that we’d be on the street by the end of the week.”

“They must have expected it,” Dr. Hesh said.

“You would think,” he said. “But in our profession, we make a habit of flouting the impossible. We have to believe that somehow, the hero will slip the net, if you follow my manner of speaking.”

“Is that a common expression?”

“Which?”

“The hero slipping the net. Envenomed Scepter, movement four, scene two. Without field research, it’s hard to know how the dramas influenced your daily speech.”

“We use that metaphor sometimes in my circles,” the man assured her.

“That’s delightful!”

He chuckled at her enthusiasm. “It’s not so common. I was saying, then. Conditions in the empire were worse than we’d ever seen them. That’s clear now, but the decay was only starting to reach us here in the heartland. The closer it came, the more we denied it. Until the Dark washed us over. How many years ago would that be, by your kind’s reckoning?”

“Almost seven hundred.”

“All one day to me,” he said. The realms under Dark were preserved in timeless permanence. Darkin lived a cycle of days that were essentially the same, repeated to infinity. To this man, his prior life was literally yesterday, although in fact centuries had passed and a new empire had risen in the wake of the emergent Dark. “It’s hard to keep a tally when we don’t age. So here we are, then. You come to study your heritage, and I get a pleasant afternoon chat.”

“You were going to tell your partners about the closure…” said Dr. Hesh, listening to Lisse giggle and whisper in the far corner.

“About the closure, yes. So I walked back from the magistrate with a heavy chin, meeting no one’s eyes, and fretting how I’d explain the catastrophe to the three of them. We’d weathered the great earthquake of 1094 and the riots of 1098, more than a few scandals in that time, and half the normal audiences were starting to scare as more cities defected outside and word started trickling in—it was the worst possible time to lose our theatre. Ours wasn’t the only one reclaimed during that time. The city was converting all public spaces to prepare for something, we didn’t know what.”

He frowned in thought. “Then I convinced myself that my partners would rather enjoy the illusion of prosperity one more day, and I wandered into a smokehouse to numb myself. I have the heart of an artist. Sometimes I savor my feelings for the story’s sake, but other times I need a fresh scroll to change my vision.”

“I’m not here to judge you,” said Hesh. She lowered her voice. “My daughter’s best friend fell sick two years ago, by Night Sun reckoning. It was sudden and very destructive. Even knowing this friend could die any time, I lied to my daughter for as long as possible. She thought Glair—the friend—was visiting relatives in another area, when Glair was really at home, festering.”

“So young to lose a companion,” the man said.

Dr. Hesh noticed the air had quickly grown more humid, but her daughter shouldn’t know what that meant. The girl hadn’t spent enough time in the Dark to learn how it magnified thoughts and feelings. “Yes,” Hesh said, her voice breaking. “She was, and still is. I wanted to shield her from the hurt and grief in the world. The physicians found that Glair had contracted the disease years before. There were no symptoms all that time, until it erupted into a fullscale war on her body. In the end I offered to smuggle Glair into your city, where I’d already been working as a scholar for some years.”

“She’s been here?”

“In an orphanage,” said Hesh. “Safe and healthy. I’ve seen her a few times since, but this will be Lisse’s first time.”

When last Lisse saw her friend, the girl lay moribund and scarred, unable to speak—a stark vision from which Lisse never really recovered. Today Dr. Hesh would offer Lisse the long-promised visit to Glair, and everything would be set right.

Reorienting her thoughts, Hesh said, “I’d like to finish our interview soon, if you don’t mind. We’re due to see Glair together shortly.”

“Indulge me a bit longer. When I walked into the main room of that smokehouse, I counted myself a wretched man. At first, the vapors weren’t effective to the task of rubbing out my despair. I didn’t see how our entertainments would survive without the theatre. And as I sat there bemoaning myself, I heard the dirge of souls coming down the street.”

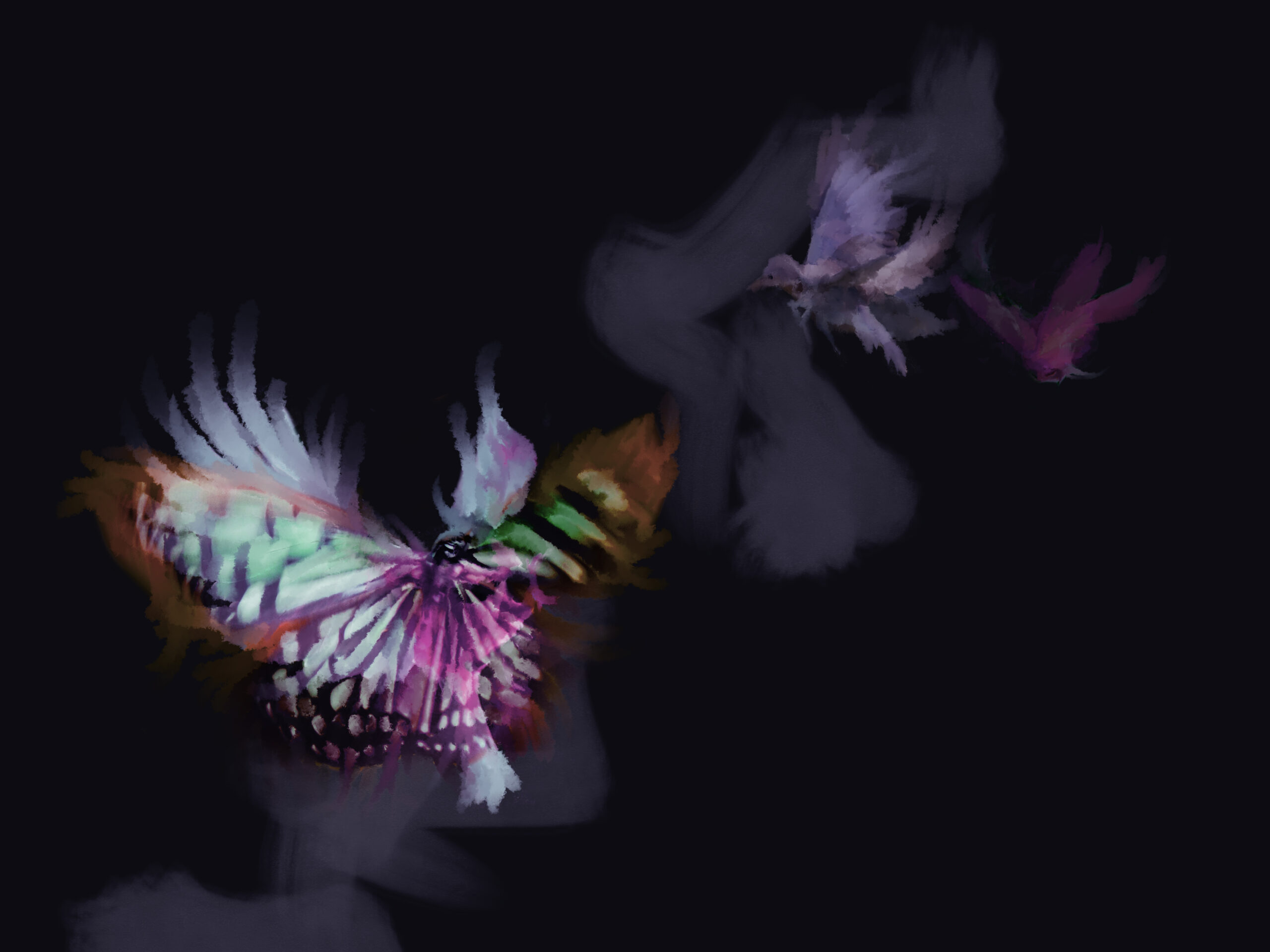

As if called forth by his words, the familiar wild music flared out like a flock of startled birds. Today’s procession was returning from its circuit through the city. The images in Hesh’s goggles sharpened with the increase of noise. She could see even the lashes over this man’s sightless eyes and paint chipping and resealing, like feathers ruffled by a breeze, on his faux throne.

Of course, “as if” was wrong in this case. A habit Hesh brought from the Light, where thoughts didn’t summon events.

“The procession was marching past at that very moment,” continued the man, “and I leapt up at the sound. A bit unsteady from the vapors, I staggered to the door and watched them pass. Then came the flash of revelation. Masks, makeup, costumes, pomp and drums. We believe we must make a great show to attract the spirit ancestors, who alone can lead the newlydead home. Otherwise the newlydead linger or wander where they shouldn’t. They get lost, like the souls here in my warehouse. Do your people believe the same, doctor?”

“Our theologies have evolved somewhat since your day,” she said, “as our two worlds have diverged. I’m not a specialist in ritual practices, although my peers tend to see a close relationship between ritual and drama.”

“How strange,” said the man. “We consider them sharp contrasts. The city would never allow someone from drama to work in ritual. It wouldn’t be an easy career transition. But I knew more deaths would come as the empire crumbled further. More deaths, and perhaps more interest in improving the rituals.”

“Improving how?”

“Our theatrical skills and resources would bring the stories of the dead to the streets. The state-sponsored dirge was all very regular and repeatable. Never did it feature the dead as characters in a performance, but our processions started doing just that. To enrich the rituals, not compete with them.”

“Was there personal meaning for you in these funerary rites?” said Dr. Hesh.

“I suppose I was glad to honor people with a final remembrance before they departed from memory.”

“You don’t think of it as immortalizing them? Helping them outlast their deaths?”

“Nay, I wouldn’t wish that. A proper ending is my satisfaction.”

Although surprised, Hesh didn’t have time to press the point. Instead she said, “Your epiphany is a prime example of what I’ve called the ‘delirium of social decline.’ You projected a way to thrive in spite of, even because of, the larger collapse you were expecting. Many people choose to ignore an impending crisis as long as they can stave it off with the illusion of their society’s health. It’s especially true for imperial civilizations claiming an ancient heritage.” She winced. “I…hope that’s not offensive. Most societies seem prone to some kind of delusional thinking. Even Lightkin think ourselves invincible.”

“I don’t like to take offense,” the man murmured.

Relieved, Dr. Hesh stretched and shot another look in her daughter’s direction. Lisse had found a pair of fluffy hats, one on her head, the other bouncing through the air with the ghost’s movements. Soon after losing their body and anchor, these creatures devolved from the people they’d been into near-mindless remnants. Over time Hesh had grown fond of the Dark’s constant susurrus of beating wings, but her daughter took an instant liking.

If feasible, she might bring Lisse more often. But the paperwork for bringing a family member was horrific, and the permit had to be renewed with every excursion.

“You seem to have a more careful view of my people than most Lightkin,” the man said. “So many of you don’t think of us being much like yourselves. Even when you honor us, we become like the actor who forgets himself for the role he’s given.”

“The historian’s duty is to humanize the past,” she said. “Thereby to guide the present. Notice I haven’t asked about the first emergence of the Dark. It’s not my focus. Many have devoted their careers to that turbulent event, and the rise of the first Night Sun after, but I’m more curious about the late momentum of the Spice Empire than its actual condition.”

“The Dark is convenient for you, then. Though I often wonder, how many of us would choose it?”

“You mean, if you had the power to keep the sun from dying?” Dr. Hesh reached for the recording device, on a table between them, to switch it off.

“Yes. It’s a legend to you, so you have a hard time understanding life in that world. If we could save the sun, on the condition that we must watch our great civilization fall apart within our lifetimes, and each alternative was presented to us—how many of us would choose to preserve ourselves at the cost of the sun? That’s our fate now. How many would choose the collapse instead, so long as they would see the sun rise and set till they died?”

She paused despite herself. “That’s an intriguing question. It might depend on how pressing death seems to the one considering this choice. There’s a saying that death is the root of all fears. If that’s true, then it’s the difference between a life free of fear, and one shaped by it.” She had seen the contrast in her little girl’s life since Glair’s loss.

“The sun was a marvel to see, but also a simple pleasure to feel. Maybe it’s my eyes gone obsolete, but what I crave most isn’t the view of bright skies, but the taste of sunlight warming my flesh. The Light you know is cold.”

“I can only dream of it. Still, you never die. You lose nothing and no one. There must be consolation in that.”

“Some,” he said, his tone slipping into bleakness. “Consider this side of it: we don’t get an ending. It’s the flaw of immortality. We rehearsed for three mortal hours onstage, scripted to resolve in one climactic breath, yet when we arrived at the final movement and the last hour, be it tragedy or whatever genre, that closure was denied us. The Spice Empire is forever falling into oblivion, but the pit is bottomless. No hope of rest. We just fall and fall. Life continues unchanged. I’ll never have another role…unless I find a spark of Light where I can die, and perhaps become a ghost.” He waved at their surroundings, where all manner of souls flittered and, in Hesh’s goggles, wove trails of light through space.

“I see. I’m afraid we need to go now,” said Hesh. “The procession will slow us on the way to see her friend, and our shuttle is due at a fixed time.”

He heaved a sigh. “Alright, I won’t keep you longer. Have we more sessions to come?”

“I think so. I enjoyed talking.”

Dr. Hesh pocketed the recording device and crossed the room toward her daughter, haunted by the dirge. It was at least a relief to see with more clarity, as her goggles translated the sound into light. She brushed aside an iridescent ghost that fluttered past her face and knelt down to touch the girl. “Hi, sweeting.”

“Mommy, is it time to go?”

“Yes, sweeting. I know it’s been so long. We’ll go see Glair now, like I promised. Is that worth the wait?”

“I liked playing with my friend.”

“Oh, good.”

Lisse said, in her smallest voice, “She wants to go with us.”

“I’m sorry, we can’t take a ghost home. It’s the rule of coming here. But they’re nice, huh.”

The girl sniffled as Hesh led her into the street, leaving behind the little warehouse where the man stored props and costumes and conducted all the funerary operations for his clients. Darkin deaths were rare, but not impossible. Sometimes the Night Sun failed to remove a stray growth of Light before it was exploited in a murder, accident, or suicide.

Despite the Darkin man’s belief, the Dark signified peace and preservation. Glair would be alive and grateful to see—or at least hug—her friend again.

They started up a flight of stairs that climbed to an upper street. Lisse was dragging her feet, and Hesh squeezed her hand. “We won’t have time to spend with Glair if we don’t hurry along!” she said. “You know I can’t bring you every time.” Her daughter would grow old while Glair would remain forever the child that fell sick. One day Lisse would choose to retire to the Dark as a wrinkled adult, and perhaps spend peaceful days in company with little Glair. Hesh smiled to think of it.

She glanced down to where the elaborate carts, dancers, and musicians marched in swirling files, while a booming voice shared the story of the deceased. Stricken by a swift and deadly disease, this little child came to us for healing. But she was scared, heartbroken, removed from all she loved, and so she chose to die regardless.

“Mommy, look!”

Hesh turned to follow her daughter’s pointing finger, and searched among the sleeping bodies in procession on the street below. “What is it, sweeting?” she said.

Before the girl could answer, Hesh found it. A small face with faint scars of a former disease, precious nose, plump lips. The Dark didn’t erase disease, only buried it until the Light should make it fresh again.

“Glair, Mommy. She said we would find her outside.”

She chose to die regardless.

“She said…Lisse, we haven’t seen Glair yet. What do you mean?”

“I did see her! She can fly, Mommy. She showed me and it was lots of fun.”

Mind reeling, Hesh stared at the young body laid out in the cart. Wearing the same wrap Glair had chosen for her voyage to the Dark. It must be a coincidence.

“Sweeting, that’s not her. She’s alive. I saw her last time I came here. She was happy to see me.” Hesh’s voice was catching. She wanted to seize her daughter and run, run until they came to the orphanage where Glair would be waiting.

Yet what if?

If a child expects to die, and she is taken from familiar surroundings to a place of strangers and total darkness, will she not search out the Light? No matter that Hesh explained she can never return. Of course, when the child finds a pocket of Light in the Dark, she goes to it. Collapses. Loses her breath. She can’t call out, and the ones who know and love her are far away. Most Darkin avoid Lights, so the girl may lie there until death claims her.

“It’s okay, Mommy.” Lisse hugged her leg.

“How can it be okay?” Hesh said, sinking down beside her girl. “Aren’t you sad?”

“Glair isn’t sad any more. I thought she was really gone. But we played when you were talking to that guy.”

Dr. Hesh savored a deep breath of the humid air. Before long, rain began misting over them, and she held her daughter in her arms, clenching her teeth against the urge to sob.